What is a Fact?

Part 1: Insights from Alfred North Whitehead's Process and Reality

Over the decades, I have been struggling to explain to others how to tell if something is, or is not, a fact. The initial impetus came from my work as an engineer specializing in failure analysis. I came from a family of people who have all enjoyed teaching at some point. Rarely have we had the word teacher as the primary definer of our profession, but we have taught math, law, herbal medicine, swimming, metallurgy, and after I started doing failure analysis, I created some training programs for my clients, so they could help me help them solve their industrial and design problems. The most important three tasks in engineering failure analysis of a component (say, a shaft, or gear) or assembly (a machine or structure) are visual inspection, background information gathering, and negotiating the specific tasks and goals of the investigation.

Over the last few years, starting during CoVid, I have been diving into the ideas of various philosophers more deeply and broadly than I had earlier in life. From Jeffrey Mishlove’s New Thinking Allowed, I learned about Bernardo Kastrup’s ideas of Analytic Idealism, then came across Bernardo in dialogue with Matthew David Segall. The moderator asked Bernardo what he thought of Alfred North Whitehead, and he said he did not understand him. Matthew Segall, if I recall correctly, acknowledged that reading Whitehead is tough going. As I have “consumed” a few more of Matthew Segall’s posts and videos and interviews, and as the political situation becomes more and more distressing, I am finding that reading challenging writing, and thinking about new ideas in general, a) helps me get through the day, and b) lets me feel like I am gaining the ability to articulate ideas that might be helpful to others.

Somewhere between teaching failure analysis and Donald Trump’s political arising, I became somewhat obsessed about being able to figure out HOW I KNOW that a fact really is a fact. People from the church I was attending at the time looked to me to explain various scientific phenomena, but I realized that their repeated rejections of my offers over the years to teach a “citizen science for the spiritually minded” class meant that there were layers and layers of foundational knowledge that they lacked, which meant that my “explanations” would be meaningless. The general level of scientific ignorance in the USA led (I think!) the Union of Concerned Scientists to a new mantra to “Trust Science.” I hated that. The whole point of science is that you don’t have to trust it. Real SCIENCE is about always keeping in mind that your best answer might be overturned. The predominant culture has turned science into a religion with dogma which is not to be questioned. I believe that the arrogance which led to this attitude is a major reason, along with the costs of scientific progress, for the backlash against science in our politics. James Tunney (who I also met through New Thinking Allowed), and others, call this Scientism. The final bump that pushed me into trying to come up with a definition of a fact was my neighbor accusing me of not knowing what a fact was. I was pretty outraged, because by that time, I had already been teaching my fellow failure analysts what a fact was for at least 10 years. But my neighbor was right. I had never really adequately defined it.

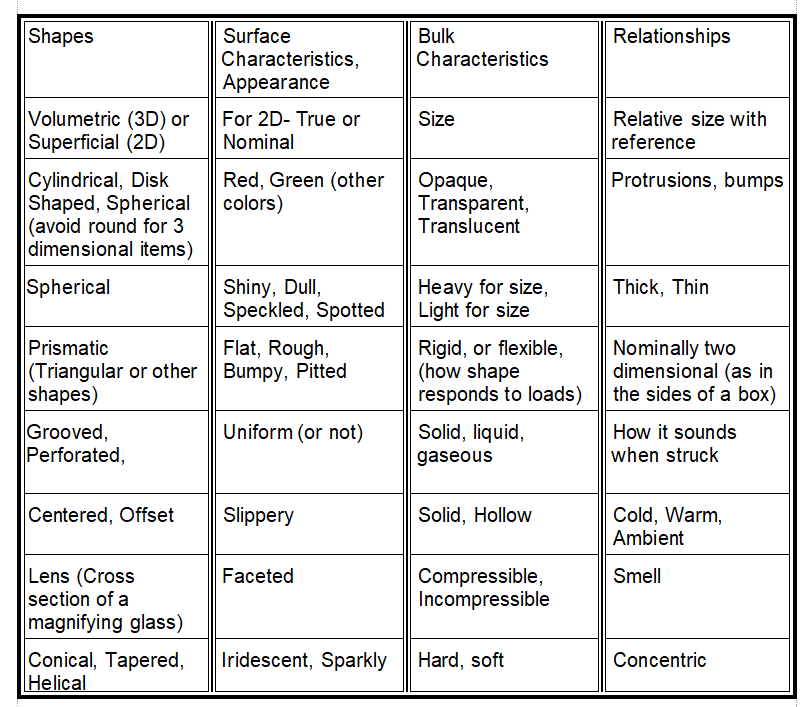

Here is my list of the types of features that I taught may be thought of as basic facts about a concrete object. Features that anyone with more or less normal vision and kinesthetic sensory function can test for themselves.

Table 1: Features of Concrete Objects or “physical things.”

1 Gives an explanation of Nominal 2D.

So that became my definition of a fact for failure analysis. Anyone with sensory function in the range of a statistically normal human (yes, we could argue about that, but I won’t here…) could determine it. It’s important to have basic facts on which we can agree. That sets the scene to explore more controversial ideas. Seeing that something is cube shaped does not require years of engineering education or work experience. Figuring out that you can squeeze a blown up balloon doesn’t either. Determining if something is slippery or not is something we learn as children, when our caregivers caution us to be careful of, when walking in a muddy or icy place. Our caregivers or friends give us sparkly toys or shoes. These are things we know, we recognize effortlessly. This type of feature may be agreed upon by people of good will wishing to communicate.

That is not true for knowing how medical researchers know what virus is responsible for which symptoms, whether the sun revolves around the earth or vice versa, or in my case of failure analysis for a shaft, what the alternating colors or shininess of strips of different colors means regarding how fast the shaft broke. Figuring these things out requires a lot of accessory, systematic, specialized knowledge. They are not facts in the basic sense that anyone can see. That’s why they are called theories, even if they are good, or even the best, working theories that we have. Good working theories are deemed good working theories because they help us get though life more successfully.

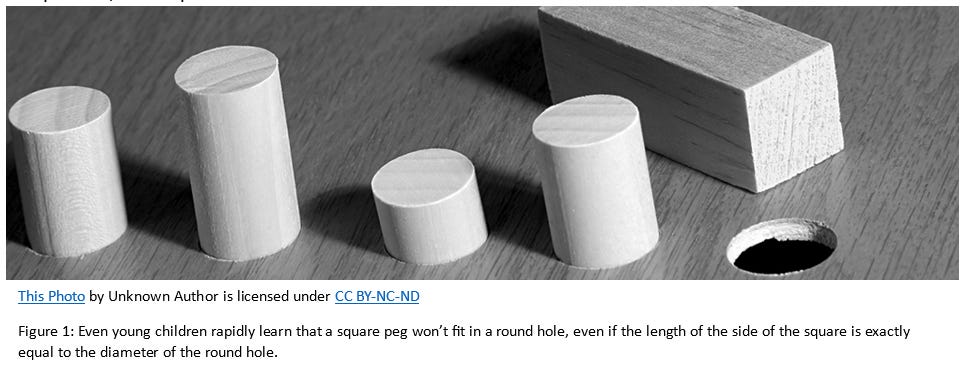

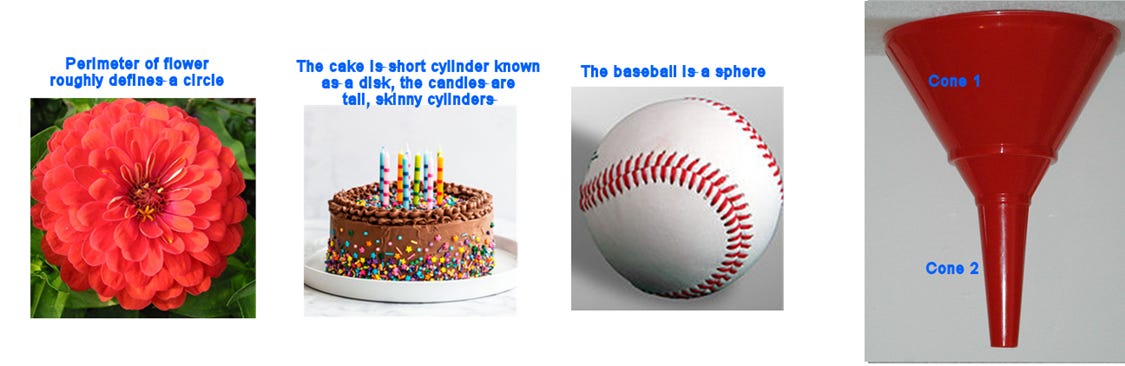

Figure 2: Different types of “Round” things.

Now, back to Alfred North Whitehead. I am starting to plow through Process and Reality. It’s slow going. But in a few sentences, Whitehead explained what I ran into as I was struggling to explain to my neighbors and the people in my church congregation how I knew that my beliefs about reality were well founded. “There are no self-sustained facts floating in non-entity.”

Giving a little more background, as he criticizes most of the philosophers since the times of Plato, we read:

“Thus, every proposition proposing a fact must in its complete analysis, propose the general character of the universe required for that fact. There are no self-sustained facts floating in non-entity.” [1978 Corrected Edition page 11]

What does this mean for us regular people? For me, it’s a nudge to remember that when you run across someone who thinks differently from you, it’s likely because they are seeing a different universe from you. And that while your universe may be closer to the “consensual reality” that we occupy, that does not mean that every element we take for granted is in perfect accord with “what is.” We all view the world through the light and darkness2 obscuring filters and the field distorting lenses of our own particular lives.3

An example of nominal 2 dimensional feature would be a skirt or a curtain, a textile what is folded in some way, not lying flat.

For without darkness, we can not see the stars.

And this brings me back to my failure analysis definition of facts and opinions based on specialized knowledge, and my personal hunt for ways to communicate with my neighbors on the far side of the political spectrum from me. It always comes back to defining the general, or at least some specific characteristics, or the universe in which those facts exist. If this is as far as I get, if this is the most precious gem I harvest from Process and Reality, it will have been worth the price. But it is my intent, by writing here, in public, about what I learned, that others may tell me how they have been able to apply this in their own lives, which will push me to keep going. On to page 13!